From the Aeneid to the Modern Mediterranean: A Reflection Between Past and Future

This Op-ed is available in Italian on "Strumenti Politici".

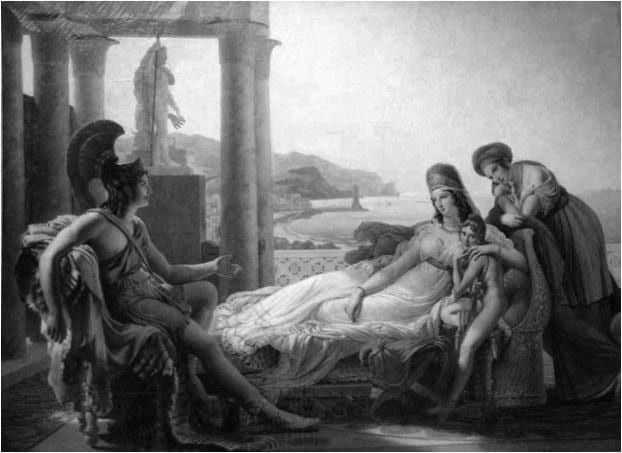

On the African shores, bathed by the waters of the Mediterranean, once stood the splendid Carthage. It is here that Virgil sets the first part of his epic, choosing this city as the stage for the tragic love story between Aeneas and Dido. After the perils faced at sea, the Trojan hero finds refuge with the Carthaginian queen, enchanted by her beauty and generosity.But the passion that arises between the two is destined for a sad epilogue. The order of the gods, in fact, commands Aeneas to continue his journey towards Italy, abandoning Dido in the deepest pain. The queen, betrayed and desperate, takes her own life, cursing Aeneas and his descendants.

Their love, born under the shadow of destiny, ends in tragedy, leaving an indelible mark on history and literature.Aeneas admires the moles, once huts, he admires the gates and the bustle and the paving of the streets. The Tyrians strive ardently, some to erect the walls and build the citadel and to roll rocks with their arms, others to choose a place for the house and to enclose it with a furrow; they choose laws and magistrates and the holy senate; here some dig the port, here others cast the deep foundations of the theater, and from the cliffs they cut enormous columns, a lofty ornament to future scenes.

(Aeneid, Book I, 421-429)

A Stage for Migrations

From the Aeneid to our days, the Mediterranean has always been a stage for migrations. A sea that has seen ancient and modern heroes challenge the waves to seek a new life. But if the epic odysseys of the past were often celebrated, those of today are too often marked by suffering and precariousness. In a café in Bardo, I met Professor Mhamed Hassine Fantar, one of the leading figures in archeology and history in North Africa. Our conversation focused on the Mediterranean, a basin that unites us more than it divides us.The professor emphasized how the fate of the northern and southern shores is inextricably linked: any change, positive or negative, has repercussions on the entire region. Most young Tunisians, 70 percent according to some polls, are just waiting to emigrate to Europe. A dream, that of the perennial search for Eldorado, which according to Fantar can be traced back to a series of historical events.

The History of Carthage

"Everything depends on the soil, not the seed. The grain, if planted in the right soil, will germinate, but it will wither if the land is not fertile," explains the eminent professor who, during his academic career, has taught ancient history, archeology and history of Western Semitic and Libyan religions at the universities of Tunis and teaches at the universities of Rome La Sapienza, Bologna, Cagliari, Tripoli, Benghazi and Leuven, as well as at the Collège de France. In this reflection, Fantar retraces the history of Carthage from its foundation to its first destruction by the Romans, from its resurrection to its second destruction by the Arabs. The current North Africa is the result of a long series of sometimes dramatic historical events."The Mediterranean, one and indivisible, needs new militants," says the professor, highlighting how the Arab world lacks above all an etymological dictionary. Because the construction of the Mediterranean must start from the study of words or rather from the study of national languages. The first language of which there is evidence in Carthage, or rather, in Tunisia, is certainly Punic, although the first archaeological evidence dates back to over 2 million years ago.

The Destruction of the Library

The Romans destroyed the Library of Carthage, saving only the "Manual of Agronomy by Mago", an agronomic treatise in 28 volumes, which refutes the idea that Carthage was only the sea, because in reality the Punic city was above all linked to the land: to agriculture, to livestock, and to the artifacts that were traded across the sea. Of this language, only the names of cities and tribes remain. "If we look at the geographical maps," suggests Fantar, "we find the same names in Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco." Hence the need to train experts, able to understand the message of toponymy.The second language, from the destruction of Carthage by the Romans in 146 BC to the second by the Arabs in 698, is Latin which will then be replaced by the Arabic language in the years following the foundation of Kairouan. The etymology of words is the key to understanding and therefore the construction of a harmonious and peaceful future, both for the northern and southern shores of the Mediterranean. "The latter victim of colonization and pre-colonization," according to the professor.

Medina

The first obstacle that this region experiences is the confusion between politics and religion. "The two domains must be distinct, although there can be no humanity without religion," adds Fantar, who, returning to the origin of names and words, explains the etymology of the word medina, formed by me and din which in Arabic means strength, authority, similarly in Greek we find dynamos. Medina is the place where the prophet received the laws from God, hence the place of authority, understood as the only force. Previously, the city was called Yathrib; for the ancient Romans, it was Yatrippa. Decisive, for the change of name, was the beginning of the Hegira (622 AD). In Yathrib, in fact, Muhammad moved, who there created the first community of Muslim faithful. For this Yathrib became al-Madina al-munawwara, 'the most enlightened city' and then only Madina.

Pre-colonization

If pre-colonization has done its damage, the two destructions of Carthage, the Pope's speech for the first crusade are certainly an example, colonization has attacked not only the intellect, but above all the feeling. If the intellect, or rather the idea can be changed easily, the emotional level is much more complicated. Professor Fantar, with his usual erudition, invites us to reflect on the complex interaction between political power and the religious sphere in the Mediterranean. Underlining the etymology of the term 'medina', he reminded us how the city, place of authority and divine law, has always been a fulcrum of identity and power. However, he warns, the overlap between these two areas has often generated conflicts and divisions. The historical events, from the destruction of Carthage to the bloodless crusades, show us how the intertwining of politics and religion can have devastating consequences, not only at the intellectual level, but also emotional.The history of Carthage teaches us that civilizations, even the greatest and most flourishing, can undergo declines and rebirths. The challenges faced by the Carthaginians, such as the Punic Wars, are distant in time, but the principles of resilience, adaptation and capacity for recovery they demonstrated are very relevant. By studying the past, we can draw inspiration to face the challenges of the present, such as climate change, mass migration and economic crises.

Mhamed Hassine Fantar recalls the fascinating anecdote narrated by Sallust about the race between a Carthaginian athlete and a Cyrenean one to establish the border between the two powerful cities of Cyrene and Leptis Magna. This gesture, seemingly simple, contains a profound symbolism: the race as a metaphor for life, competition, the search for a limit. But above all, it represents the attempt to reconcile two worlds, two cultures, two visions of the world, within a single geographical space. An image that still resonates today, in a Mediterranean that continues to seek a balance between its different components. Today, as then, the tensions between East and West, between North and South, are putting the region's cohesion to the test. However, just as in the past, dialogue and collaboration can be the key to overcoming these divisions and building a common future.